Hegseth's Deadly Fiasco: Eugene Fidell Explains

- Former JAG Working Group

- Dec 3, 2025

- 20 min read

Original interview conducted by Jennifer Rubin at the Contrarian. here

As more information emerges on the deadly September 2 strike against a boat in Venezuelan waters, experts warn that it may constitute an illegal military action. Determining the exact role that Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth played has proved difficult.

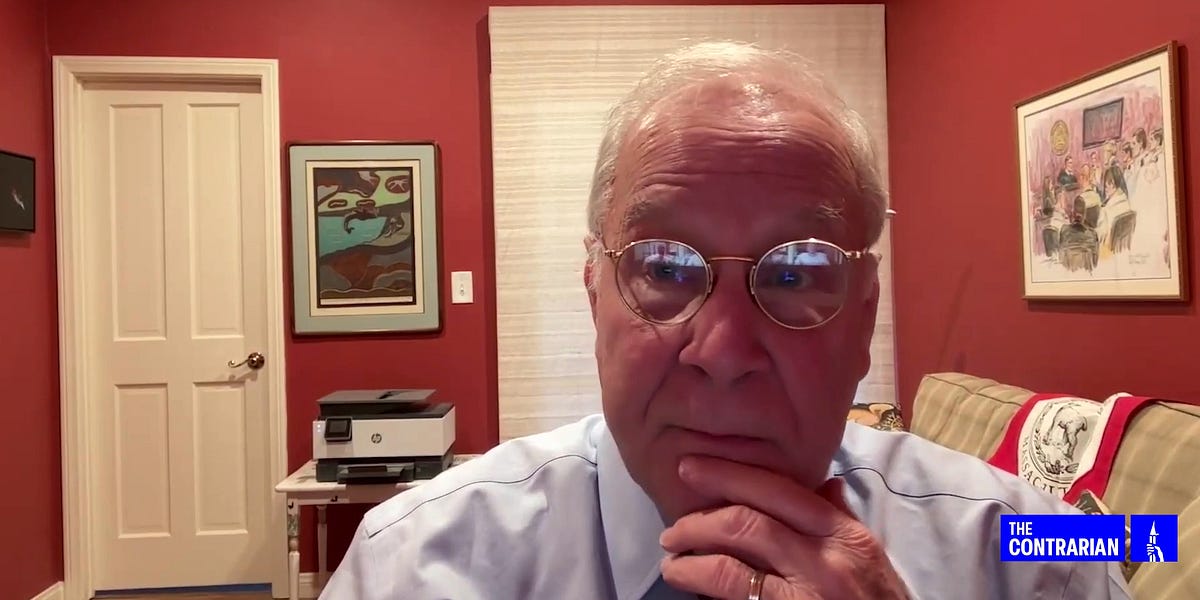

Military justice expert Eugene Fidell joins Jen to help us unmuddy the waters. First, it is necessary to determine exactly what happened. Only then can we consider the next steps towards justice. Considering this administration’s track record on oversight, it is doubtful that Hegseth will ever be held accountable for the scope of his responsibility in the lethal strike.

Eugene R. Fidell is a senior research scholar in law at Yale Law School. In addition, he is of counsel at the Washington, D.C., firm Feldesman Leifer LLP, where his practice focuses on military law. He served in the U.S. Coast Guard following graduation from Harvard Law School, and co-founded the National Institute of Military Justice. His books include “Military Justice: Cases and Materials and Military Justice: A Very Short Introduction.” He has edited the Global Military Justice Reform blog since 2014 and has taught at Yale, Harvard, NYU, and the University of Virginia.

The following transcript has been edited for formatting purposes.

Jen Rubin

Hi, this is Jen Rubin, Editor-in-Chief of the Contrarian. I am delighted to welcome Gene Fidell. He is a former JAG from the Coast Guard. He is now at Yale, and one of the leading experts in military justice, which is unfortunately a very popular topic these days. Welcome, Gene, it’s great to see you.

Gene Fidell

Nice to see you again.

Jen Rubin

So, based upon what we know so far, can you take us through what your understanding of the basic sequence of events of this particular strike on September 2nd was?

Gene Fidell

Right. That story begins before this particular strike. It began with, the development of an operation plan within the Pentagon. With the approval of the Commander-in-Chief, that’s President Trump. And the… apparently… and I’m confident, the active involvement of the Secretary of Defense, Pete Hegseth. This particular, mission that had, such, disturbing consequences began, it was probably in the planning stage for a week or 10 days. That’s speculation. And it obviously, went south. And, the question I think everybody is confronting is. like, okay, what, what actually happened here? Who’s responsible for it? how do we get to ground truth if there are any obscure or unknowns? And what is to be done?

So those are all questions. And unfortunately, virtually every one of those questions, remains clouded in the fog, not of law, of war, but the fog of facts. As a result of, you know, military operations generally are not put on the front page of the paper, or, you know, broadcast to the world at large. There are classification problems, what’s secret, top secret, and so forth. And we also have an administration that is extremely, economical with information, and such information, as, despite its frugality, does emerge, is often, fuzzy and raises more questions than it answers. So, let me give you an illustration.

President Trump the other day, actually, no, President Trump in October, made a comment that the purpose of the exercise, basically, the overall exercise, was to, kill drug traffickers. There’s all kinds of category questions that have to be unpacked, but that’s the sort of starting point. He’s the commander-in-Chief, and you know, frankly, President Trump talks too much, and when he does talk, it’s unreliable.

So, the other day, there was a news clip of a passing interview, I believe on the airplane, some journalist asked him, well, what about this boat strike? And he said, well, I don’t know anything about it. And then he continued to talk, and said that, you know, he discussed it with Secretary Hegseth, and Hegseth had told him that, you know, he didn’t order the second strike. And the president, as a lie detector, you know, announced that Secretary… he believed Secretary Hegseth’s account.

But, he added, again, you know, continuing to talk, that, oh, if there was a second strike, well, I would never have approved that. Or words to that effect. So, you know, quite what his take is on this is impossible to pin down. And, you know, a passing conversation in the passageway of an airplane is not the way to try to get a reliable account from him. Even on a good day, it’s impossible to get a reliable account from him. Fair enough. So, let’s set aside that.

Secretary Hegseth had overall responsibility under President Trump for this entire operation. It’s a string. This is the mission that went really sideways, is one of a number, and we don’t know how many, if any, others had similar mishaps, but, if you can call a mishap within a mishap, you know, it may be a misuse of the term. We don’t know precisely what Secretary Hegseth said either in writing or orally, and if it was orally, who was in the room? We don’t know the answer to that question.

If there were other people in the room, as I imagined there were, those people are witnesses. There is no particular reason to say Secretary Hegsteth’s unsworn statement is gospel. Then there’s, Admiral Bradley. Admiral Bradley was not co-located with Secretary Hegseth, and neither of them, that I… that’s my understanding. And neither of them was at the scene of what I’ll call the crime, if you forgive the idiom. So there was some communication.

The communication, was either by message traffic. For which there’s a written memorial, or orally over some kind of classified communication system. But which was probably recorded. But it exists. I mean, so, what was he, what was he told? And what did he say in response? Now, I have to digress here for one second, if you don’t mind.

A hero of mine is President Grant. And one of the great books of the 19th century was The War Memoirs, Wartime Memoirs. Great read. Everybody should have read that at some point. He had a couple of major strengths. One was he was a terrific horseman. He’s a great, great horseman. And he was also a terrific writer of orders. When General Grant issued an order, there was no doubt what he meant. If he was giving discretion, he gave discretion. If he had a particular, you know, thought in mind, he would tell the subordinate exactly what to do, when, and probably how to do it.

With that by way of background, it’s critical that whoever looks into this, and I want to get to that, has access to the written documentation that came from the Secretary to Admiral Bradley, and then what went down the line to subordinates.

Now, to get personal for a minute, I live most of the time a knife throw from the Norman Rockwell Museum in the Berkshires. And there’s a famous Norman Rockwell illustration of the telephone call. Where a number of people are talking to one another, one after another, one after another, one after another, passing a message. And of course, by the end of the multiple-party conversation, the message is entirely unrecognizable.

Jen Rubin

Yes.

Gene Fidell

Back to the main event. What happened here? Was whatever the message originated as faithfully communicated to personnel down the line? We don’t know. Okay, so that’s apiece of it, And then… but I think one of the other items on my, you know, initial comments, Jen, was what is to be done? I mean, who can investigate this? So let’s take a minute to consider the alternatives.

To the extent that there’s a possibility of exposure under the Federal Criminal Code, for a murder or some other offense committed on the high seas. That’s the responsibility of the U.S. Department of Justice. And any federal felony, of course, can only be prosecuted, we know this from Mr. Comey’s current litigation, can only be prosecuted if there’s been an indictment returned by a federal grand jury. Indictments don’t generally emerge. In fact, they almost never emerged spontaneously from a federal grand jury. You could have a runaway grand jury, but it doesn’t happen. So, some federal prosecutor, either from Main Justice or from the United States Attorney’s Office, would have to go before a grand jury and say, I want you to indict X, Y, and Z for these murders on the high seas. I don’t know about you, but I don’t think this Department of Justice is going to do that.

Jen Rubin

Not happening.

Gene Fidell

Which leads to, well, what about the next Department of Justice, which may be you know, dominated by, you know, led by a different political party. Well, yeah, there’s no statute of limitations. Pertinent to this. But what if President Trump pardons everybody? We know that he’s profligate, that’s an understatement. I’ll say profligate, with pardons.

Jen Rubin

Yes. Yes.

Gene Fidell

So, he could do that, and everybody could go home, and that would be that. Nothing happening here, everybody’s great, everybody did their job. They did the right thing, we knocked off some drug traffickers, there were a few people killed in the process, it wasn’t perfect, no mission is perfect, nothing’s predictable, and it’s on the high seas, and thanks, everybody, and start handing out medals, and life goes on.

Pardons Now… That’s a terrible… that’s a terrible thought, that military personnel have to be put in a position in terms of moral injury. It’s bad enough, the moral injury of being involved in an operation that has gone so badly sideways. But the moral injury of, at the end of your, let’s say, 30-year career. You get your certificate, thank you for your service. There is a form that’s very lovely, and you put on your wall. And in your, you know, official papers, there’s a pardon from the President of the United States. That would be a hell of a way to wind up a military career.

So, what are the other alternatives? Federal grand jury, we talked about. How about the military? Well, any person can put people on reports. Say, I believe an offense has been committed under the Uniform Code of Military Justice, and then it goes into the military chain of command, and the military chain of command, the first commander to get it, could take it and throw it in the wastebasket. That’s unreviewable.

Or, could initiate a preliminary inquiry, a very informal inquiry, send somebody out, you know, get some officer to make, you know, question people and so forth. Okay, and then what happens? Well, if it seems that there’s some offense under the UCMJ, okay, then somebody has to decide whether the charges… somebody has to prefer charges, which is a technical term. It means somebody subject to the UCMJ has to sign a form swearing to charges. Who’s gonna do that? Who’s gonna do that? Assume somebody did it. Assume you had some disgruntled retiree, or somebody who’s about to leave the service and says, I won’t be in on Monday, Chief, but here’s a charge sheet. Give it to the yeoman. Well, that’s not going to go very far, but… so you can see, it would be really very puzzling if this Pentagon actually pursued a UCMJ matter.

Now, what are the other options? There’s the Inspector General. Well, as I recall, the President eviscerated the Inspectors General. I don’t know what the current arrangement is at the Pentagon, who the individuals are. I’m sure there are estimable people there, but gee whiz, this is… you know, you’re investigating the President of the United States and the Secretary. That’s a tough one, and I don’t know, in this climate, after the surgery that President Trump did on the IG system, that there would be much public confidence in the outcome of such an investigation.

So what else is there? There is something called a court of inquiry. Back down memory lane, do you remember when the submarine USS Greenville surfaced under a Japanese training fishery vessel off Honolulu, sank it with loss of life? It was a major stink, maybe 20 years ago or so. And the Navy convened a court of inquiry. Very formal. Much of it, the unclassified part, was conducted in public. The media were there covering it. And, it was pretty adversarial. A wonderful lawyer named Charlie Gittins defended the CEO of the Greenville. It was a big deal. And that’s… That’s rarely done, but as I, you know, think back. About, you know, naval catastrophes over the years, I think this would be warm as an occasion for a court of inquiry.

Now, do I think that’s gonna happen? I do not. For all the foregoing reasons. So we’re left, therefore, with the Congress of the United States. And to their credit, the leaders, chairs, and ranking members of both the House and Senate Services Committees have taken a lively interest, understandably, in this controversy. And I think it is now incumbent on them. It’s a very interesting challenge that they have. They need to actually talk to people. Some people may not want to talk to them. I don’t believe they can grant immunity. Because they don’t have prosecutorial power. So, they can subpoena you, but you can take the fifth, or the equivalent under military law. They’ve got to talk to people. People may not want to talk to them. Well, how do you get around that? Somebody else can grant immunity. Who would that be? The Department of Justice? Not this Department of Justice. The Defense Department? Not this Defense Department. of Justice.

You can subpoena documents. What documents? Well, we’d like to see the OLC opinion, the Office of Legal Counsel Legal Opinion, that kicked this entire mission off. Well, that’s classified. You’re gonna get that? You may get to see it. You’ve probably already seen it, but it’s gotta become public for the public to have any confidence in this entire, inquiry. How about all the message traffic? How about the logs? Rough and smooth. How about all the notes that anybody made?

Then, you’d want to have a really solid hearing without a lot of evasion. Without a lot of the funny business that we’ve seen in various nomination hearings, whether it’s judicial nominations or, you know, other nominations. So that’s really a challenge, and what you would want to do, and touch wood on this, you would hope that that hearing would not involve a lot of the posturing that, tragically, we’ve come to tolerate from congressional hearings and, you know, get real about it. Now, all of that said, there’s another wild card, and I apologize, Jen, for this long salute.

Jen Rubin

No, it’s very helpful.

Gene Fidell

There’s another dimension to this, which is, in military justice, there’s a doctrine called unlawful influence. It used to be called unlawful command influence. Congress is not supposed to meddle in the administration of justice on a retail basis. And there are times when you could talk about a generic issue, potential legislation, you know, a review of major national security initiatives, and both strikes qualify. And it may be hard to disambiguate the generic issues from the administration of justice, the potential administration of justice, because there may be people who may be subject to disciplinary action.

So that’s a challenge, which I would hope and expect that the leaders and the staff of the Armed Services Committees would be mindful of. So there’s really a balance, and I feel torn on that, but I do think that we don’t want to throw out the military justice baby with the boat strikes bath water.

Jen Rubin

All right. Let’s go back to the military operation itself. Since Congress is going to be in there anyway, having a hearing, it seems almost inevitable, and certainly desirable, for them to look at the overall basis for this military action. And many experts, you included, have discussed that if it’s not really a military operation at all, then we move from War crimes to the civilian military, civilian justice system, which is murder or other homicides.

Based upon what we know. there does not seem to be an armed conflict with these people. And part of the problem is these people are not well known, identified, there’s no indication that they have a unified command, there’s no indication they are intending to physically attack the United States. So how do we reach some kind of clarity on whether we are in a war at all, and whether the military justice system should apply, or the civilian justice system should apply?

Gene Fidell

Well, there’s a… there’s a premise in what you just said that I want to slightly push back on. You could have military justice applying whether or not you deem this to be an armed conflict. Okay, so I… I’m sharpening the pencil.

But it’s important to not get off on category errors. So, let me, let me address what you just said. For good reasons, there’s been a great deal of discussion about war crimes, the law of armed conflict, and all of that, a double tapping, and, you know, was the second strike, you know, that it’s a war crime to shoot people who are doing the backstroke, trying to get away from their boat that’s on fire, or is, you know, sort of splinters. That’s entirely understandable. Why is that? Because that’s the way this has been advertised by this administration. Okay? That advertisement, that is false advertising. It’s not an armed conflict. The only armed conflict in the area is the one this country is threatening to conduct against the sovereign government of Venezuela.

Jen Rubin

Right.

Gene Fidell

And you can’t make an armed conflict, and then say, well, everything’s an armed conflict, look at this armed conflict! There is no armed conflict going on, aside from our saber-rattling, and the aircraft carrier and everything else that’s steaming around the Caribbean, threatening, President Maduro. Who is no prize either, but that’s neither here nor there.

But it’s because this has been… this course has begun under the rubric of armed conflict. It’s been inevitable that people have responded. Experts have responded, in a way. It’s perfectly understandable. You know, that’s the way the issue has been begun, and it’s continued, understandably, on that course. And the long and short of that analysis is this isn’t an armed conflict. But if it were, this would be a war crime.

Jen Rubin

Right. And if it’s not in the military code of justice, you can still prosecute people for murder.

Gene Fidell

No, no, but that’s back to my other point. Whether or not it’s an armed conflict the CMJ still applies to the uniformed person.

Now that we’ve gone through the looking glass, and we’re now talking about law enforcement, you have to analyze it as a law enforcement matter, and the answer is, by the way, we’re still doing drug enforcement the old-fashioned way. We’re busting people, we’re taking people into federal district court, we’re grabbing the goods, the evidence is overwhelming, it’s a good mission, it’s been professionally developed over decades. And what you have is, an extraordinarily excessive use of force. Lethal force. Lethal is one of Secretary Hegseth’s favorite words.

Jen Rubin

Yes, along with Kinetic, whatever that is.

Gene Fidell

Lethal, right, under circumstances that no responsible public official in any democratic society, or any organized government would, tolerate. You don’t at the outset, have a right to destroy a vessel that you suspect may be running drugs. There are only two offenses around the world that the Law of the Sea recognizes as Universal offenses: Piracy and the slave trade. Drug trafficking is not on that list. Yes. So just set that thought aside. So this already, this begins under a cloud. Now, we are anxious, and countries do make their best efforts to suppress drug trafficking. How do they do it? If you have a vessel that you suspect is running drugs and it’s in international waters, the high seas?

What you do is you attempt to cause it to stop, or heave to, to be a little nautical about it. How do you do that? You come alongside, and you have somebody with a loud hailer, and say. Stop your vessel! Probably in Spanish in this environment. Not hard to do. Or, you might have somebody with a flag, a spotlight signaling. Or, if it were a big enough vessel and they knew this kind of stuff, there’s flag hoists, flag signals that you can do. Or you can even drop a note on the deck of the ship from a helicopter, if you happen to have a helicopter around, saying, stop your vessel. What if they ignore you, or none of this works, or it’s a howling gale? Whatever. What you do is you have a sniper in the bow of your ship. Who’s got really good eyesight and a scope, and the sniper disables the steering. You don’t machine gun everybody on deck. You don’t destroy the wheelhouse, or the pilot house, or the bridge of the vessel, the cockpit. That’s… that’s what you do.

And just to give you one small illustration, there was a… there was an incident not involving the U.S, it involved the UK and Denmark, two friendly countries, never mind Greenland. Two friendly countries. And they were having a fishing dispute. This is about 1960 or so. And the Danes used excessive force against a British fishing vessel called the Red Crusader. And it caused a tremendous international stink, and arbitration resulted, there was a judgment, money was paid, and… You know, this… I cite that as simply an illustration. That’s what law enforcement is about. Law enforcement is not about identifying somebody, I think that person is running drugs, bang, you’re dead. You don’t get to do that. You don’t get to do that on Fifth Avenue, and you don’t get to do that in the Caribbean Sea.

Jen Rubin

Right. Now, we have, as you say, many, many questions to be asked, and there’s much documentation that should and probably does exist. What are the kinds of questions, that you would be asking of people in the chain of command to determine what the exact order was, what was said, what their motivations are? How do you, because you’ve been in military court, what are the kinds of questions you’re posing to these people under oath?

Gene Fidell

That’s assuming they’ll talk to you.

Jen Rubin

Yes. Yes, assuming they haven’t all taken the fifth.

Gene Fidell

Taking the fifth, and that’s assuming somebody’s not willing to give immunity so that you can work your way up the chain of command. This has to be very methodical, it can be boring. Who was in the room? What did each person say? Did anybody keep any notes? Was the person smiling? Give me the exact language, please. I need the exact language. Was colorful language used? Did somebody… You know, use an epithet about the suspects? Did anybody, did anybody check with higher authority while you were in the conversation?

Jen Rubin

Did you check with the lawyer?

Gene Fidell

Thank you for reminding me. One of the… one of the questions is, did anybody consult a lawyer? If so, what was the nature of the consultation? What constraints, if any, were placed on that that consultation, what record was made of it? Or was anybody told not to put something in writing, for example? Was any effort made to go up the chain of command to query the, Lawfulness of any particular order, or any part of an order. It’s this kind of thing, and you want to use a vacuum cleaner in this kind of interrogation. Interview, let’s say interview.

I want to know everything. That’s the thing. I’ve been a trial counsel, which is a military prosecutor. I’ve been a defense counsel. You want to know everything. And you want to know how this operation is conducted. The thing about litigating, this is true of any kind of litigation, the thing about litigating is the litigator has to become an expert in other people’s business.

Jen Rubin: Yes, exactly, which maybe Congress people don’t have. It might be a good idea to have Perhaps committee counsel there to guide the question, though this is a perennial bugaboo of mine that, in general, you do better having committee council rather than elected officials do the questioning, but, I doubt they would see.

Gene Fidell

They would probably want to get a technical interrogator. Yes. Somebody who knows about these kinds of missions, maybe retired personnel, you know, somebody, a ship driver, or a drone person, and so forth. somebody who’s been in maritime law enforcement, for example. And possibly make that person staff. Make that person a staff counsel.

But this is not… this is not, you know, like trying a case to a jury. This has got to be very deadpan, no posturing. Just the facts.

Jen Rubin

Right. Tell us a little bit about the obligation of more senior officials and civilian officials to shield lower-level people from potential liability themselves. What we have heard from Pete Hegseth, over the last couple of days, seems to be an effort in some blame shifting, that I didn’t say anything about going back. I didn’t say anything about X, Y, and Z. Talk to the Admiral, who’s a wonderful man, but he’s really the one you should talk to. both as a legal matter, as a command matter, as a moral matter, does that work? Can he get out from whatever responsibility by simply saying he did it?

Gene Fidell

That happens not uncommonly, I think, in criminal prosecutions. I didn’t shoot him. My pal over here shot him. I wasn’t the trigger man, he was the trigger man. It was his idea, it wasn’t my idea, I was just driving the car, whatever. So this is… that’s kind of… that’s human nature, and one does what one can. The notion of scapegoats did not originate in this environment. There is a case that actually is fairly pertinent to this. Some years ago. Well after the Vietnam War ended, The USS Dubuque. Came upon a boatload of boat people who were fleeing Vietnam. Perhaps you remember it.

And they rendered…the Dubuque rendered some modest assistance, and then sailed on. the… boat with the… the vessel with the boat people. Came to a terrible pass.

Jen Rubin

Yes.

Gene Fidell

My recollection is that it led to cannibalism. And the U.S. Navy prosecuted the captain of the Dubuque. He was taken to a general court martial. He was convicted. he received the reprimand. He didn’t go to Leavenworth, but he received the reprimand, and his otherwise sterling career, he probably would have become an admiral, was at an end. And one of the things he said afterwards was that he was being made a scapegoat.

Jen Rubin

There is a certain code and a reputation, that the American military is proud to have. It is, that’s why we have a military code of justice, that’s why we have, the system that we do. It’s why allies will trust to engage with us, will trust to give us, Some kind of intelligence assistance. What does this do to the reputation of the military in general, the willingness of other military to interact with us? This seems to be a systemic stain, as far as we can see right now, that is, really a blight on our military, unless we can get to the bottom of this and resolve it in a satisfactory way.

Gene Fidell

Our allies are already taking a hike. We know that some of them, at least, are not going to cooperate. Some of that is simply attributable to the unpopularity of, President Trump, elsewhere. I had an email the other day, from a friend who used to be the Judge Advocate General of a Western European country. I’m not going to name the country or the individual, but it was… It was kind of… not more in sorrow than in anger, it was in sorrow and anger about what’s unfolded here.

And people around the world, actually militaries. It’s very interesting dealing with military personnel. From a host of countries. They have a great deal in common across national boundaries. In some respects, they have more in common with one another than they have with Very true. A civil society in their own country. Occasionally, I’ve seen that. There… the, revulsion that people around the world, including in our allies, are feeling is a penalty that is incalculable. Our relations, our friendly relations, with so many countries on which we have rightly prided ourselves it has been squandered in this and other respects, by the administration. I mean, it’s a fact. I mean, the whole tariff war. There’s an interesting use of the word war, misuse of the word war. That’s crazy.

And, you know, the corrosion that kind of stuff as well as the current controversy in the Caribbean is… I don’t know how you put Humpty back together again. The settlement that we’ve had in terms of relations with other democratic countries is the result of, A hundred plus years of work, diplomacy, cultural bonds, and so forth. And it’s like a sledgehammer. Wrecking ball may be the right… it’s like a wrecking ball has been taken to that set of unwritten, but very real relationships. Trust and confidence. It’ll be restored, but it’s going to be a major effort, and it can’t happen too soon.

Jen Rubin

And it would seem the first step would be to hold people accountable, and to show that we do have a system in which people are held responsible for their actions. So, that does underscore, as you say, how serious, the investigation that Congress is going to undertake. Thank you so much, Jean. It has been an education. We will continue to learn, I’m sure, more than we ever thought we would know about military justice.

Gene Fidell

Before we wrap up, though, Jen, I want to thank you. The entire country is going through a kind of national teach-in on this subject. The country is getting a crash course in the law of armed conflict, military matters generally, what it means to have a unitary executive. What does that mean for accountability? We know what it means for power. What does it mean for accountability? It’s an interesting conversation you might want to have with somebody in that part of the forest. But thank goodness that our civil society, including the media, remain free and open, and that people like you are able to contribute to public understanding.

Jen Rubin

Thank you. Thank you, and thank you for your service and your role in educating the public. We’ll look forward to having you back soon. Take care.

Gene Fidell

Thank you.

Comments